Recreations, not Replicas

Our goals and aspirations

|

We strive for something more than mere visual resemblance to the historical weaponry in the swords we make. Our goal is to reproduce not only the visual aspects of the originals to a high degree of precision, but also make swords that will handle and perform like the originals.

For anyone who has had the privilege to hold an antique sword, the "feel" of an original sword is unmistakable -- a feeling rarely found in modern day replicas. The term "replica" is often used to represent a look-alike, sometimes made with moderate or low aspirations to authenticity.

Peter documenting original swords at the

Swedish Army Museum |

We prefer to call our products "recreations" rather than "replicas," as they will be more than something that merely looks the part. To achieve this, it is necessary to carefully observe hidden aspects that are available only through a personal experience from the historical originals, expressed in an exacting documentation.

Albion's new line of products are based on swordsmith Peter Johnsson's years of work observing, documenting and analyzing original swords in museums and private collections throughout Europe. Peter has been allowed to document and handle swords in the permanent displays, as well as the hidden treasures in the storerooms that only few get to see.

Trained as a graphic designer before becoming a smith, Peter's eye for detail captures both the aesthetic character of the original as well as aspects like mass distribution and dynamic balance, down to details like gradual changes along the blade in volume, cross sectional geometry and edge angles.

These insights and collected data have been critical to our ability to actually "recreate" a sword from an original -- making a restoration of the piece as on the day it was new: gleaming sharp, powerful in its presence, with an agile and responsive balance.

Peter documenting one of the hidden treasures in the

University of Uppsala storeroom |

A sword is a seemingly simple yet very complex tool -- evolving from the time the first bronze sword was cast and changing dramatically the first time a piece of steel was forged into a blade. It is a process refined over millennia, an art passed down from Master to Apprentice. Most of this art is now lost to us, though we can learn much by studying the objects left behind by the tide of time.

If we look carefully at these accomplishments of the ancient masters, we can testify not only to the skill and craft by which they were made, but also about the thoughts that went into their making.

In his research, Peter has discovered that among all of the blades he has examined firsthand, there are interesting similarities in the way proportions correlate. Having these rules of proportion to work with, not just measurements of individual originals, makes it possible for us to create anew swords that are truly like siblings to any historical sword of the same type.

Another of the hidden treasures in the University of Uppsala storeroom, recently documented by Peter and Eric McHugh |

We know that in the Middle Ages, engineering was a refined art. Mighty castles and lofty cathedrals across Europe testify to the ingenious application of harmonic proportions. Not only engineers but also master craftsmen were aware of how the beauty of form is vital to function.

Thus, the same rules of proportions seen in architecture were also used in the building of musical instruments and sea going ships. The budding art of typography in the late 15th century is another example of how widely the ideas of harmonic proportions were applied.

Just how these golden rules of harmony were best put to use might many times have been at the core of the secret knowledge of the Masters. We can see the result of their insights and skills in surviving works of art and architecture. But also, interestingly, it seems that the best of sword-smiths and cutlers from early times were familiar with, and worked according to, these ideas as well.

Stage 1: Research and Documentation

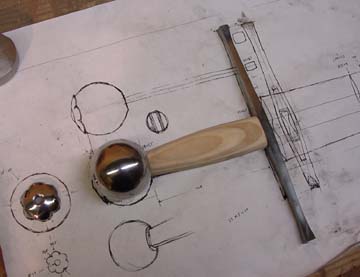

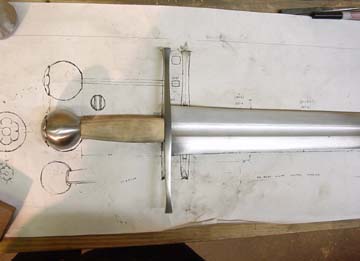

When Peter documents a sword, he typically devotes at least an hour and a half to the examination. He takes measurements of the weight of the piece and other vital statistics (such as placing of balance and pivot points, etc.), and traces the sword on to paper from several perspectives.

Peter makes precise notations of edge angle and radius of fullers and hollow grinds. As many as 20 or 30 full-length and detail and perspective photographs are taken of each piece. These are complimented by drawings of pommel, grip and cross-guard to show the shape and character of these parts in a way that photographs cannot convey.

Peter and Eric discuss a new sword model |

Eric McHugh, was recently able to visit Peter in Sweden and accompanied him on several "white glove" research trips to some prominent local museums. Working as a team, they were able to document over 20 original pieces in the storerooms, most of which have never been researched or published before.

Stage 2: Design and Development

The next step, which ranges from straight forward to very complex, is reconstructing the original as it was when first made. This incorporates full size drawings of the finished sword, drawings of different parts in various stages of completion together with a design sheet specifying how everything is to be processed and put together.

Peter's detailed drawing of the Solingen sword Peter's detailed drawing of the Solingen sword |

The blade alone can be a complex drawing, having as many as 7 or more cross-section measurements along its length. By measuring several original swords and comparing how distal taper and cross section change along the blade, it is possible to make comparisons and see not only the amount of variation in specific measurements, but also how these typically relate to each other.

Recognizing the typical proportional relationship between different parts of the blade makes it possible to develop designs today that will share both general and specific aspects of original swords.

This knowledge helps both in the reconstruction of museum pieces and the designing of the new generation line of swords.

The main difference between a forged recreation of a piece that Peter makes for a museum display and the Albion recreations is mostly the production starting point of hilt components and blade blank.

When forging a sword in his smithy, Peter creates a "blank" or basic shape that establishes the distal taper and the basic shapes/volumes and distribution of mass. This blade blank must have dimensions that allow for the final shaping by grinding after heat treat.

At Albion, the blade blank is milled in a CNC mill to the same basic shape and specification as would a forged blank. By using a mill a highly defined blank can be made more efficiently and consistently than by forging each blank by hand.

Steve and Peter discuss a blade blank |

In both cases the final quality of the sword is a direct result of the awareness of shape and dimensions as well as the control of the process. To use the potential of the CNC machine in blade production means that the skill and insights of the smith are translated to the program guiding the milling process. When the milled blank is incorporating the important details and proportions that are shaped during the forging, a high degree of consistency is possible while keeping the final swords very close to the characteristics of the forged blade (and the originals that are being reproduced).

Steve Fisher, our CAD/CNC designer, has broken new ground on several fronts in his ability to translate the properties of a properly made forged blank into a machine-milled blank. This requires translating Peter's detail drawing first into a CAD drawing, and then into the volumes of coding needed to run the computerized milling machine.

Steve and Bob running a milled blank

Steve and Bob running a milled blank |

When the initial blank is made, usually in mild steel, it is sent to Sweden for Peter to double-check and do experimental grinding, along with a set of aluminum tang plugs for prototyping hilt components.

If the finished blade meets the meticulous measurements and standards, we make a first production prototype run.

If fine tuning is needed, we go back and reprogram the milled blank.

As an example: the blades for the first three Museum Line swords (Tritonia, Solingen and Brescia) were programmed and prototyped three times before we achieved a blade blank that incorporated all of the properties we sought.

A partially completed NextGen milled blank

A partially completed NextGen milled blank |

In the meantime, Peter uses the aluminum tang plugs to carve wax originals for the hilt components (guard and pommel), using the now finished blade to calculate volume/mass so balance and pivot points are ideally placed for optimal handling and performance. The waxes are actually made a few percentage points larger than final, in order to account for shrinkage during the molding and casting process.

Peter´s experience from the forging of hilt parts allows him to carve the waxes so they express the same character in shape and volume a similar forged pommel or cross would have.

Target weights and volumes are set that the final cast and finished part must adhere to, or we begin the process again. With three of the Museum Line swords (Solingen, Brescia and Svante), Peter carved the waxes twice, and the components had to be molded and cast twice (an expensive and time-consuming process), in order to achieve the proper volumes and dimensions, due to unexpected (but miniscule) additional shrinkage in the final cast parts.

Stage 3: Prototyping and Testing

Once the initial prototype blade has been approved, we do a short run, usually one to three blanks, in our steel of choice, 1075.

Jason heat-treating a prepped milled blank |

We put each of these first run blades through the prepping, heat-treating and production grinding process, to ensure that we can accurately recreate the original in every aspect, consistently.

Jason Dingledine, working from Peter's specifications, develops a heat-treating regimen suited to the steel and the blade type. Each blade is individually heat-treated by hand in an exhaustive process.

Once the blanks have been successfully heat-treated and have the proper temper, Jason then hand-grinds each blade to final specifications and finish.

Jason grinding a blade blank |

A very important aspect of the final grinding is the shaping of the the edge: a biting sharpness that has to be resilient. The shape and nature of the edge vary between different sword types according to their intended function.

A sample blade is then run through a torture test, to make sure that the blade will perform to the same standards, or better, than a period original in its prime.

This involves several test of the steel, the heat-treating/tempering, and the edge geometry.

A test blade from the first run is repeatedly bent in a vise until it either sets or breaks. The number of bends that it can withstand without deformation and setting are determined.

The edge is repeatedly struck against the rolled edge of a steel barrel in order to test the temper and the edge geometry -- if the edge does not fail during this exercise and can be refurbished with only minor regrinding or polishing, it will most likely stand up to any use a period original would have withstood when new. (See the results of the testing of a Tritonia blade here.)

In parallel, Eric McHugh develops the process for finishing and fitting the cast components. Even investment cast fittings require a great deal of hand-finishing to bring them up to our standards of fit and finish.

|

|

|

Eric hand-finishing the guard for the Tritonia |

|

|

Tritonia parts prepped for final assembly

Tritonia parts prepped for final assembly |

The components of each sword are carefully fitted to the tang of the sword -- both the guard and pommel are wedged into place before peening the rivet block.

In this process, it is ensured that the guard will not loosen or the pommel twist, as is often found on replicas that have threaded pommels or are held by the peen to a round rod welded to the tang.

The peening is done under heat, which gives us greater control of the final shape and character of the peen, and does not cause the tang end to split or otherwise bend or deform as it sometimes does when cold-peened.

|

|

|

|

|

Close-up of the hot-peening |

The assembled Tritonia before the grip covering is applied

The assembled Tritonia before the grip covering is applied |

The grip is then fitted after the sword is assembled, as it often was done traditionally.

We use stabilized birch for a grip core, which is less likely to swell or shrink in ambient humidity.

Over this core we apply linen cord and then top grade calfskin to achieve the look and feel of surviving period grips.

This method of grip assembly produces a comfortable, secure and long lasting grip that will age gracefully.

The type and dimensions of the grip, the placement of the risers and other aesthetic considerations are based on Peter's research of surviving examples of the type and period.

Stage 4: Production Development

In historical times the blade smith and the grinder of blades were often separate professions, and for good reason. This was a way to make blade production rational, using well-developed skills by specialized craftsmen.

Peter meeting with staff on final assembly specifications for

the Tritonia and Brescia Museum Line swords |

The situation at Albion is actually quite close to how work was organized in the armouries in medieval times:

Blades were produced by a smith (the CNC machine is responsible for this in most cases at Albion) to be defined by the grinders.

Cutlers were doing the mounting of the blades and hilt components and a scabbardmaker was responsible for scabbards and belts.

It is fascinating to see how the ancient method of organizing the production of arms and armour still is a viable process today.

We swordmakers today all face the same challenge: To make swords that are functional and true in both handling and aesthetic qualities, while working in a modern world with modern materials.

High quality work is only possible when these four components are in harmony: materials available, production methods, aspired goals and the attitude of the maker.

We are now concentrating our efforts on two sword lines:

The first is comprised of exact recreations of museum originals based on Peter's documentations: The Museum Line.

Here we select outstanding examples of the European sword-makers' art to be recreated to their full splendor. In those cases when the original is damaged or has lost some of its mass and volume due to corrosion, it is very helpful to have experience from other originals to achieve a realistic reconstruction that is in line with the character of the original.

In addition, we are reintroducing the Albion Mark line with a next generation of swords designed by Peter based on a "composite of several originals, blending the aesthetics, functionality, and blade design properties into a perfected representative model of its type" -- not recreations of specific single originals, but swords true to their historical counterparts that would have been indistinguishable from their period fellows when they were new.

Harmonic proportions as seen applied in historical swords is our guiding principle in design and construction.

By working according to these ancient principles, we strive to make available swords that express strongly both the aesthetics of a specific historical period as well as being fine examples of the handling characteristics and performance of good quality swords through the ages.

|

| |

|