The contemporary swordmaking industry is rife with marketing terminology

such as "battle ready," "battle worthy," "warrior grade" etc.

None of the terms are truly meaningful -- for anyone trained in

the martial arts, a rolled up magazine can be used as a weapon,

capable of serious damage, and could therefore be considered "battle

ready."

Any replica sword, even a stainless or mild steel sword-shaped object,

can do serious damage if used as a weapon.

We coined the term "fully functional" a few years ago to describe

the standard that our swords are intended to meet -- but what does

that mean?

To us, that means a sword that meets or exceeds the standards

set by the originals we recreate or are inspired by.

Anything that a Medieval sword should be expected to be in: materials,

weight, balance, proportions and dimensions," look," "feel," edge

geometry, fit and finish, cutting ability and most importantly,

safety.

All of these categories comprise the intense specifications that

our swords are expected to meet.

Some of these measures are difficult to describe and even more difficult

for a potential customer to see in static photographs on a website.

However, there are a few of those hidden "bones" and safety

features that can be demonstrated. In the following series of articles,

we hope to illustrate these features.:

Construction

We use the same construction methods that were used to make an original,

period sword.

We’ve tried various other methods, but from our own experience,

not only is this the most authentic method, but from a practical

standpoint the safest and most durable means of assembly. As it

turns out, Medieval swords were constructed this way for a reason.

Guards and pommels are permanently wedged into place on the tang.

This ensures that the guard and the pommel will not shift in position

with time and use (and in fact, as with period swords, will oxidize

or "rust" into place, making the attachment even more permanent).

The end of the tang that protrudes from the end of the pommel is

then "hot peened" -- which means the end of the tang that shows

at the top of the pommel is heated and then gently hammered and

expanded (often into a recess in the top of the pommel) to form

the "peen block," which is then either blended and polished into

invisibility or filed and shaped depending on the demands of the

period.

These hilt components are therefore permanently in position before

the wooden grip core is applied -- the peening is a final security

measure, but is not what holds the assembly together. The wooden

core, since it is added after the assembly is complete, bears none

of the pressure from the rest of the hilt assembly.

We no longer use a "compression" assembly method on our historical

swords -- the compression method means that from the end of the

tang to the guard, force is constantly applied through either a

threaded nut (which is, in some cases, the entire pommel, in other

cases a pommel nut) or through "cold peening" where the flattening

of the very end of the tang against the pommel is used as a means

to compress the entire hilt assembly (pommel, wooden grip and guard)

against the shoulders of the blade.

Even the first generation Albion Mark swords have been converted

to this new (or should we say old) method of assembly. "Compression

assembly" - either with a threaded tang or cold peening -- is not

sufficient to meet our standard of "fully functional."

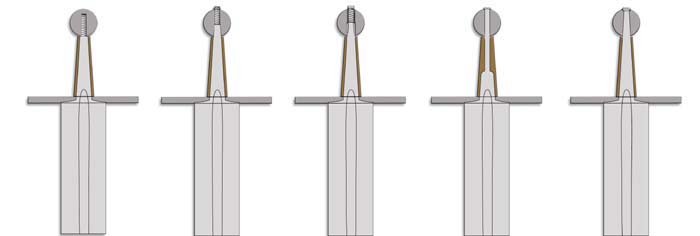

There are two methods of compression assembly, as mentioned above:

the threaded tang and pommel, and cold peening. We have used both

of these methods in the past, and have consequently discovered the

inherent problems with these methods. The illustration below shows

(in somewhat exaggerated form) these different methods.

|

|

Threaded

Compression

|

|

Recessed

Pommel Nut

Compression

|

Cold

Peened

Compression

|

Wedged/Hot

Peened

|

|

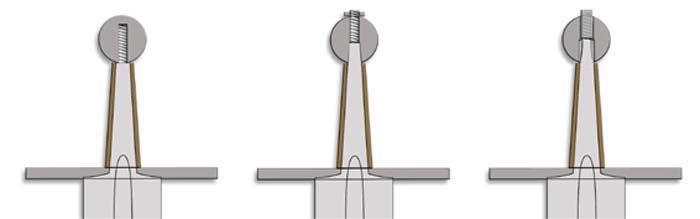

Why we don't use threaded tangs and pommels

We have found that the threaded tang has several inherent weaknesses.

The diameter of the threaded portion, by definition, has to be substantially

smaller than the overall dimensions of the tang, in order for the

assembly to be fitted together.

In addition, if you do not use some sort of "pommel nut," much more

of the tang must be drastically reduced in thickness for the pommel

to screw completely down and tighten the assembly.

With any threaded assembly, the assembly will loosen over time and

will require re-tightening. This will happen as the sword goes through

a "breaking in" period, where the compression of the hilt assembly

forces the guard to seat more firmly on the shoulders of the blade.

Though this would be considered normal with this type of assembly,

having the guard wedged firmly, and permanently, into place when

the sword is first assembled is preferable.

This compression of the hilt assembly also puts much of the stress

on the wooden grip, the weakest part of the sword.

Wooden grips are also prone to changes in dimensions from humidity,

compression and wear. This also means that, if the dimensions of

the grip change due to the above factors, the threaded pommel may

no longer be in line with the rest of the hilt assembly when re-tightened.

|

|

Threaded

Pommel

|

Pommel

Nut

|

Recessed Pommel Nut

|

|

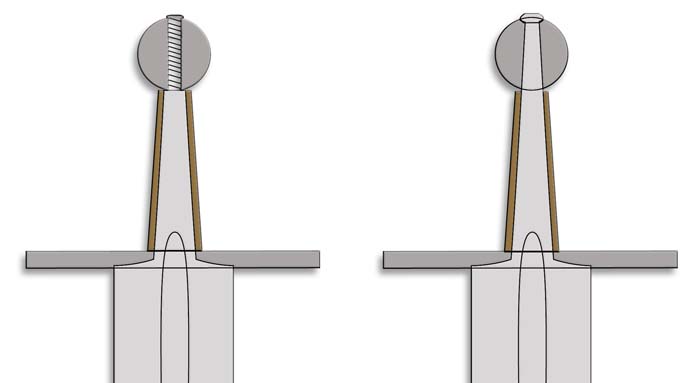

In the first two years of making Albion Mark First Generation swords,

we used a combination of threading and cold and hot peening. This

is where the last inch or so of the full tang (no welds) was ground

down and threaded. The pommel was then screwed on to the tang, and

the protruding tang peened down over the top of the pommel, for

additional security and to lock the pommel into position.

In mid 2003, we began converting all of the FirstGen swords to wedged

components and hot-peened assembly, with the grips added as the

last step (as with the NextGen swords).

|

|

2001

- mid 2003 First Gen Sword Assembly

|

NextGen Assembly

|

|

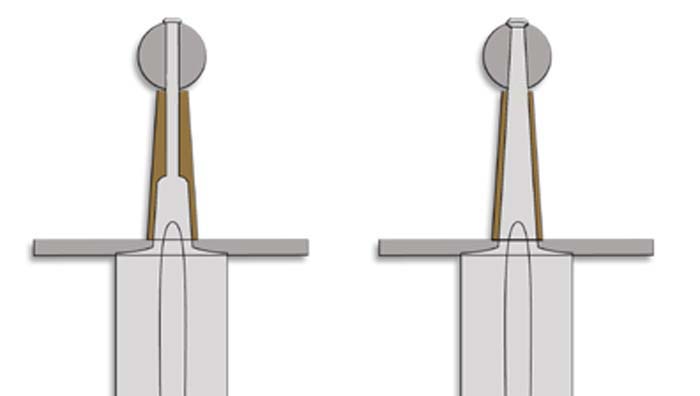

Why we don't use cold-peened assemblies

Another compression method is a peened assembly, but one where the

peen is the method of holding the assembly together.

These generally have to be cold peened, because the grip is added

before the pommel is put into place. Applying heat in the

peening process under this method would scorch or even burn the

grip. To facilitate cold peening, a round mild steel bar is often

welded onto the end of the tang (sometimes comprising the majority

of the tang) so that it passes through a hole (often round) in the

pommel. Mild steel is softer and more malleable, and thus can be

peened by hand without using heat.

This cold peened compression assembly method is prone to the same

sort of issues that a threaded compression assembly has. Due to

the changes in a wooden grip from ambient humidity, compression

and wear, the cold peened assembly can (and most likely will) loosen

over time. The guard will become loose and will rattle. The pommel

will twist and turn on the round mild steel rod.

Under heavy use (such as cutting or Western Martial Arts practice)

the mild steel rod can bend (breaking or splitting the grip) or

even break at the weld point inside the grip.

The only remedy for this type of assembly that has become loose

is to "re-peen" and further compress the assembly -- which can weaken

the wooden grip (sometimes cracking or splitting the grip core),

put more stress on the tang weld (possibly cracking or breaking

the weld), or possibly bending the mild steel rod.

|

|

Cold

Peened Compression

|

|

Wedged/Hot

Peened

|

|

Albion swords are guaranteed for life against defects in materials

and workmanship. If the hilt assembly should ever become loose through

normal use, it will be repaired for free (with appropriate shipping

charges.).

|